all the best for 2009 to all readers…

Creating a Higher Education Common Space in Southeast Asia?

I’ve asked the question before whether ASEAN was becoming like the EU. I agreed with former ASEAN Secretary General Severino who answered that it is “most likely not. At least not exactly”. Now we can ask another question: is the ASEAN starting its own Bologna process? It appears to be doing so…

I’ve asked the question before whether ASEAN was becoming like the EU. I agreed with former ASEAN Secretary General Severino who answered that it is “most likely not. At least not exactly”. Now we can ask another question: is the ASEAN starting its own Bologna process? It appears to be doing so…

The Australian reports on a meeting in Bangkok last week:

Arguing the case for an extensive overhaul of co-operation and compatibility involving 6500 higher education institutions and 12 million students in 10 widely differing nations is no easy task; and it’s particularly onerous if the deadline for implementation is 2015.

Five of its member countries were asked by SEAMEO RIHED to explore the possibility of a higher education common space in the ASEAN region. Summarising the findings, Malaysia’s Higher Education deputy director-general Yusof Kasim told the conference that:

there was broad agreement that harmonisation was beneficial, at least among those who were aware of the philosophy.

We don’t want to have one system but compatible and comparable systems. We can agree on certain standards, the most important thing is the outcome. Equivalency was crucial but it should be equivalency of outcomes rather than years spent earning a degree.

These initial discussions definitely sound similar to the ones at the start of the Bologna process. Considering the diversity of higher education systems in the ASEAN region – mixtures of English and American systems, sometimes with a Dutch, French or Spanish flavour and adapted to local cultures and on top of that, a huge variety in terms of quality – it will be a considerable task. I do believe that in the end it can be very beneficial to the ASEAN member countries and their universities. Although I think that seven years might be a bit over-optimistic, I definitely welcome the initiative. Let’s see whether – in ten years – we’ll be talking about the Bangkok Process…

Academic Salaries around the World

There have been quite some controversies about the salaries of university leaders, especially those in the public sector. Philip Altbach and his colleagues from the Boston College Center for International Higher Education have now published a report comparing the salaries of academics around the world. Here are the results, summarised in one single picture:

There have been quite some controversies about the salaries of university leaders, especially those in the public sector. Philip Altbach and his colleagues from the Boston College Center for International Higher Education have now published a report comparing the salaries of academics around the world. Here are the results, summarised in one single picture:

Conclusion? It pays of to work hard in order to get to the top, especially in South Africa, New Zealand and above all, Saudi Arabia. Not so in France and Germany (surprise?). Furthermore, an advice for academics who aspire to have an international career and want to maximise their salaries: look for extreme weather conditions. They would be best of to start their career in Canada and end up in the global classrooms in the Saudi Arabian desserts.

In addition to offering high salaries for top academics, Saudi Arabia is also actively recruiting scholars from Europe and North America. Global Higher-Ed has a post on a faculty recruitment video of the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology. Conveying a ‘unique semi-territorialized live-work-play message’ they target a mobile “world class” faculty base to come and live, work and play in Saudi Arabia. I’m sure that an average monthly top-level salary of US$8,490 helps. But then again, there are other things that count as well…

Philantropy & Higher Education

Universities are becoming popular with donors. A recent report from private banking firm Coutts in association with The Centre for Philanthropy, Humanitarianism and Social Justice University of Kent showed that in the UK, rich donors are more likely to give to universities than any other good cause. The Coutts Million Pound Donors Report (pdf) indicates that higher education received 45 donations of over a million pounds in 2006-2007. The total value of million-pound-plus donations to higher education was £296.5 million. Of direct donations over 1 million pounds in the UK, 42% went to higher education, folowed by Health (13.8%), International Aid (11.5%) and Arts & Culture (8.2%).

Universities are becoming popular with donors. A recent report from private banking firm Coutts in association with The Centre for Philanthropy, Humanitarianism and Social Justice University of Kent showed that in the UK, rich donors are more likely to give to universities than any other good cause. The Coutts Million Pound Donors Report (pdf) indicates that higher education received 45 donations of over a million pounds in 2006-2007. The total value of million-pound-plus donations to higher education was £296.5 million. Of direct donations over 1 million pounds in the UK, 42% went to higher education, folowed by Health (13.8%), International Aid (11.5%) and Arts & Culture (8.2%).

The Financial Times discusses the issue and asks whether rich people should be giving their money to institutions that also receive millions from government and are in some cases quite wealthy. The fundraising director of Oxfam Cathy Ferrier seems to concur and her words show that there is fierce competition in philanthropy land:

“The higher education sector have very effectively used their contacts, despite the fact there’s state funding for this stuff”. She suggested that rich donors liked schemes which were “highly tangible, relatively visible and close to them”, such as university buildings that “they feel are their legacy”.

The country of million dollar donations is of course the US. According to the Chronicle, the country’s colleges and universities raised $28-billion in private donations in the 2006 fiscal year, $2.4-billion, or 9.4 percent, more than in 2005. Stanford receiving 400 million from Wiliam Hewlett; David G. Booth donating 300 million to the University of Chicago business school; Ratan Tata giving 50 million to his alma mater Cornell, etc. But also outside the Anglo-American world multi-million dollars are being donated to universities. The Singapore based Lee Foundation donated 50 million to the Singapore Management University – matched by the government with 3 S$ for every donated S$. Coffee magnate and Adecco chairman Klaus Jacobs for instance donated 200 million to the private International University Bremen. Compared to all this, the Netherlands has a long way to go. In 2005, all education and research received 277 million Euros, with 232 coming from business (see Geven in Nederland 2007, pdf).

As for Ferrier’s critique, I think that needs some nuance. Giving 300 million to a business school in order to see your name attached to it – yes it became the University of Chicago Booth School of Business – is not necessarily helping humankind progress all that much. But on the other side, donations for scientific research on HIV or cancer or research on other pressing issues are not necessarily in conflict with donations for health or international aid. Ratan Tata’s donation to Cornell for instance was given for agriculture and nutrition programs in India and for the education of Indian students at Cornell. I’m sure even Oxfam wouldn’t disagree with those objectives.

Foreign Students and the Global Competition for Talent

The OECD recently published a very interesting report on skilled migration and the diffusion of knowledge: The Global Competition for Talent: Mobility of the Highly Skilled. This publication can be seen as a follow-up of the 2002 report International Mobility of the Highly Skilled. Here’s a short summary of the summary:

The OECD recently published a very interesting report on skilled migration and the diffusion of knowledge: The Global Competition for Talent: Mobility of the Highly Skilled. This publication can be seen as a follow-up of the 2002 report International Mobility of the Highly Skilled. Here’s a short summary of the summary:

“International mobility of human resources in science and technology is of growing importance and can have important impacts on knowledge creation and diffusion in both receiving and sending countries indicating that it is not necessarily a zero-sum game.

Receiving countries benefit from a variety of positive effects related to knowledge flows and R&D. But sending countries can also experience positive effects. Much of the literature on highly skilled emigration focuses on remittances and brain drain but emigration of skilled workers can also spur human capital accumulation in the sending country. Brain circulation stimulates knowledge flows and builds links between locations. Diaspora networks can function as a conduit in these migration flows so that all countries can benefit.

Most OECD countries are net beneficiaries of highly skilled migration but there are significant variations. Students are increasingly mobile as well and often leads to skilled migration, both short and long term migration. Some evidence suggests that immigrant HRST (Human Resources in Science and Technology) contribute strongly to innovation.”

Skilled migration is an increasingly important rationale for the higher education internationalisation policies of national governments (and of the European Union as well). In this global competition for talent, Australia and Canada have actively linked the recruitment of foreign students to their skilled migration policies. This approach is also increasingly chosen by European countries. Particularly in the science and technology related fields, skill shortages are becoming apparent and the benefits of (cultural) diversity for innovation are recognised.

And if you need a highly skilled and diverse body of professionals, why not start with foreign students? At Nuffic we recently published an appeal for an increased attention for internationalisation. In this appeal, the skilled migration approach is clearly apparent (see here for the Dutch booklet, or here for the English translation). Obviously, we are of the opinion that such policies should not come at the expense of developing countries…

The new OECD report shows again that such policies can create benefits for both the sending and receiving countries. This goes in particular for emerging economies where the opportunities for brain circulation are present. Other studies – like this world bank report – show that it are the least developed countries that suffer most from the brain drain because brain circulation does not occur in these countries. Here, skilled migration policies should be accompanied by compensating and mitigating policies for the sending countries (see this CGD publication for some ideas on this issue).

THE Ranking 2008 by Country (again)

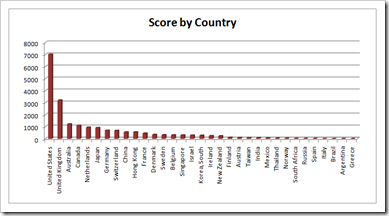

Like last year, I tried to look at the Times Higher education university league tables from a national perspective. I gave a score of 200 for the number one university (Harvard) and 1 for the number 200 (the university of Athens) etc., and than aggregated these scores for every country.

Like last year, I tried to look at the Times Higher education university league tables from a national perspective. I gave a score of 200 for the number one university (Harvard) and 1 for the number 200 (the university of Athens) etc., and than aggregated these scores for every country.

The graph below shows that the United States and the United Kingdom are again superior in the Times rankings, followed by Australia and Canada. The Netherlands is the first non English speaking country, followed by Japan and Germany. The main difference however compared to last years results is that the number of countries represented in the top 200 has increased. The group is now joined by countries like Greece, Argentina, Thailand, Russia and India.

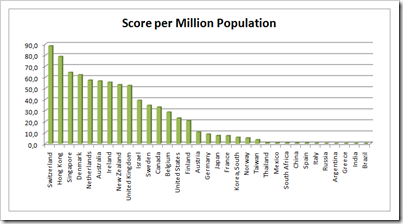

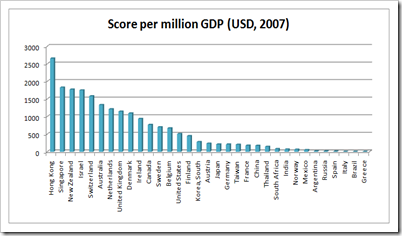

But of course…size matters and it’s easier to have many well performing universities in a large country than in a small country. So here is the result if we take population into account.

This of course works well for the small states like Switzerland, Hong Kong and Singapore. The Netherlands again comes fifth in line. If we control for GDP instead of population we get a similar picture. Here however, Hong Kong clearly outperforms the rest.

For what it’s worth….

German students and the European Court of Justice

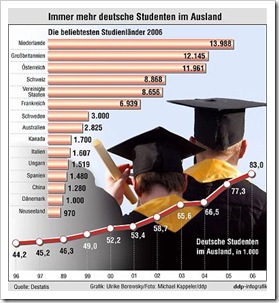

German students are stretching the scope of European rules in national higher education systems. The last few years have shown a steady increase of German students in its neighboring countries. The number of German students in German speaking countries like Austria and Switzerland have increased. However, the most important destination for foreign students is the Netherlands with almost 14,000 students in 2006 and at least 16,750 in 2007 (pdf), making it also the largest group of international students in the Netherlands.

German students are stretching the scope of European rules in national higher education systems. The last few years have shown a steady increase of German students in its neighboring countries. The number of German students in German speaking countries like Austria and Switzerland have increased. However, the most important destination for foreign students is the Netherlands with almost 14,000 students in 2006 and at least 16,750 in 2007 (pdf), making it also the largest group of international students in the Netherlands.

I recently wrote about a German student, Jacqueline Förster, who claimed Dutch financial support for the period she studied at the University of Maastricht. Now there is a German student appealing for the European Court of Justice in order to be admitted to the Medicine programme at an Austrian University. The case of German students in Austrian medicine departments has been addressed here a couple of times. See the posts on Europeanisation by stealth and the one on more Europeanisation.

Since the last post on this issue, two important developments took place. First of all, Austria got permission to keep their quotas for German students in medicine programmes for a five year period (until 2011). And secondly, the Austrians have abolished the student fees in 2007 – after introducing them in 2000. The quotas are now being contested by the German student. And considering the free education in Austria, universities are fearing an unmanageable rush of German students (‘ein kaum bewältigbaren Ansturm’, as the Vice rector of the University of Salzburg put it).

Of course, the students can’t be blamed for this. They are just exercising the rights given to them. And don’t understand me wrong. I think it’s a good thing that students can make their own choice in the university where they want to study, whether that is in their own country or in another European country. In a European system where higher education is still predominantly publicly funded, and funding is arranged on a national scale, coming from national taxes, this type of mobility however might become unsustainable. That is, if it’s distributed highly unequally.

This doesn’t mean that we have to stop the mobility, but it does imply that we seriously have to look at other funding arrangements. In some countries, like the Netherlands, student financial support is already ‘portable’ for students, meaning that students are eligible for Dutch student support, also if they study abroad. This idea could be extended to student funding.

The portability of student funding within Europe should be a serious option here. In this case that would mean that Germany would fund the German students’ education in the Austrian university. This however would require a common policy, agreed upon by all member states, or at least a large majority of states. Politically it will be hard to reach agreement on an issue like this. But it’s better than the option of doing nothing and letting the ECJ determine the course of higher education in Europe.

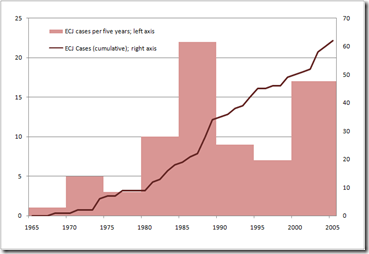

Of course it is the ECJ’s job to interpret and observe the rules. But it is about time that the Member States agree on the extent of these rules and put the decision-making process back where it belongs: in the democratic European or national parliaments. The last decades has seen a growth in the higher education related cases brought to the ECJ, especially in the 1980s and in the first part of this decade (see below). This is particularly interesting because formally, the EU has no real authority over higher education. Nevertheless, in these cases, the Court has considerably extended the competencies of the European Union in the field of higher education. And for those that think that this expanding role of the ECJ is just an isolated case for higher education: it clearly is not.

Source: The Emergence and Institutionalisation of the European Higher Education and Research Area Forthcoming in 2008, European Journal of Education 43(4)

THE/QS World University Ranking 2008

Tomorrow’s that day that many university leaders dread. Have they gone up in the rankings or not? For some, rankings may even determine whether they will receive their bonuses or not. But most of all it’s the day for your Vice Chancellor or university president to criticize league tables even though secretly it’s the first thing he or she will check in the morning…

Tomorrow’s that day that many university leaders dread. Have they gone up in the rankings or not? For some, rankings may even determine whether they will receive their bonuses or not. But most of all it’s the day for your Vice Chancellor or university president to criticize league tables even though secretly it’s the first thing he or she will check in the morning…

Yes, it’s time for the fifth edition of the Times Higher Education World University Ranking of 2008. Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd, the company responsible for the ranking, claims (again) that the methodology is improved. They are even so blunt to say that ‘the rankings have established themselves as an accepted benchmark of quality’. I beg to differ…

Yes, it’s time for the fifth edition of the Times Higher Education World University Ranking of 2008. Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd, the company responsible for the ranking, claims (again) that the methodology is improved. They are even so blunt to say that ‘the rankings have established themselves as an accepted benchmark of quality’. I beg to differ…

One issue at least seems to be resolved, that is the volatility of the THE ranking (compared for instance with the relatively stable Shanghai Ranking):

The final results will see more countries represented among the top 200 institutions, with Continental Europe beginning to make more of a mark than in previous editions. But there will be less volatility this year, thanks to the change in statistical methodology introduced in 2007. Single outliers no longer have a disproportionate effect on the overall ranking.

The world university ranking will be published here and here tomorrow morning…

3rd Birthday

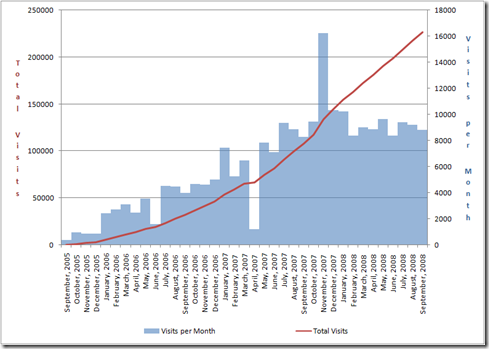

The blog turned three a couple of days ago: at the 28th of September 2005 I started this blog. I had started my postdoc at Sydney Uni earlier that year and wanted to avoid drowning in theories and concepts and lose touch with what was really happening in the global world of higher education, science and innovation. That has definitely worked and therefore it’s a good thing that many PhD students started blogging, and actually, nowadays many academics are writing about their research and their academic life.

The blog turned three a couple of days ago: at the 28th of September 2005 I started this blog. I had started my postdoc at Sydney Uni earlier that year and wanted to avoid drowning in theories and concepts and lose touch with what was really happening in the global world of higher education, science and innovation. That has definitely worked and therefore it’s a good thing that many PhD students started blogging, and actually, nowadays many academics are writing about their research and their academic life.

I’m still managing to create a few blog posts a month but unfortunately posting is getting less frequent since I left academia and moved elsewhere. Yet, it’s still good to see many people find their way to the blog. Somewhere this summer, I got my 200,000th visitor.

It’s always interesting to see what brings people here. Clearly, the most popular search terms are related to the university league table of the Times Higher. The peak in the chart is caused by a little scoop I had in November, presenting the Times Higher ranking before it was officially published. At least I hope that the people arriving at my blog looking for these rankings take the time to click through the more critical posts on the methodology, risks and consequences of ranking. The THES University Rankings 2008 are expected on October 9…

But fortunately there are also people looking for other things. Although in some cases these search terms really make you wonder… Here are a few examples:

- Herrings apparently communicate by farting. why?

- Dutch people are dumb

- 5 requirements to become u,s. president

- Person speaking japanese backwards and somebody speaking dutch backwards

- is eric beerkens from Indonesia?

European Institute of Innovation and Technology: Go!

Excellence needs flagships! That is why Europe must have a strong European Institute of Technology, bringing together the best brains and companies and disseminating the results throughout Europe. That is how José Manuel Durão Barosso introduced the European Institute of Technology about two and a half years ago. Today was the inaugural meeting of the first Governing Board of the EIT.

Excellence needs flagships! That is why Europe must have a strong European Institute of Technology, bringing together the best brains and companies and disseminating the results throughout Europe. That is how José Manuel Durão Barosso introduced the European Institute of Technology about two and a half years ago. Today was the inaugural meeting of the first Governing Board of the EIT.

The Board’s 18 high-level members, coming from the worlds of business, higher education and research all have a track record in top-level innovation and are fully independent in their decision-making. The Board will be responsible for steering the EIT’s strategic orientation and for the selection, monitoring and evaluation of the Knowledge and Innovation Communities (KICs).

After discussions on whether the European version of MIT would become a virtual institute, a brick and mortar institution or something in between… After a study claimed that a European Insitute of Technology was actually not necessary… After feasibility studies had been neglected….

After the decision for the establishment of the EIT was formally taken and published in the Official Journal of the European Union in April earlier this year… After its name was changed into European Institute of Innovation and Technology… After beautiful Budapest won the race and became the official location of the EIT  in June… And after the EIT’s first Governing Board was officially appointed on 30th July 2008…

in June… And after the EIT’s first Governing Board was officially appointed on 30th July 2008…

It is now time to get to work!

The only thing still missing is a real logo. As long as there is none, I’ll just keep on using the one I have been using for the last years. Looks familiar, doesn’t it?